This whole journalism thing was always No. 3.

No. 1 was centerfield. But when you can’t hit, can’t throw and can’t run, it’s time to move on to No. 2.

No. 2 was to sling my guitar over my back, head to Wyoming and play the blues for 60 years or so. A reverse Dylan. That was at least remotely possible.

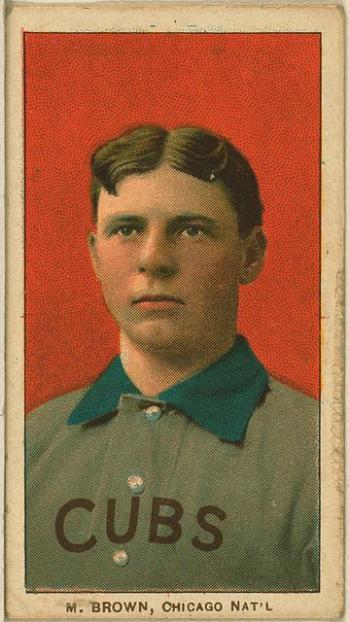

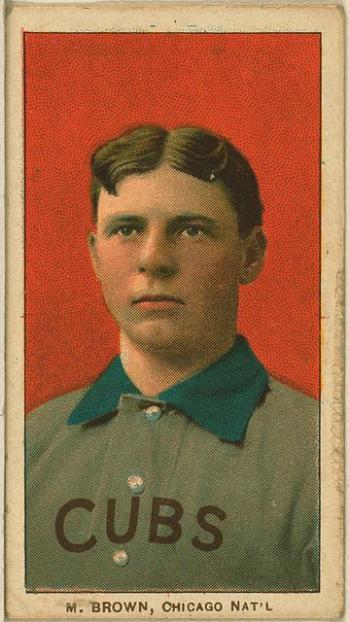

No. 3 was journalism. And that’s where Mordecai (Three Finger) Brown comes into the picture. If not for him, I might be strumming a beat-up old Gibson on a subway platform.

It’s April 1972, my senior year in college. I’m sitting in my room playing the blues, avoiding my books, and the phone rings. It’s my high school pal’s mom, and she’s asking me if I’d be interested in working in the sports department at the New York Post. They’re looking for a kid who can type and spell and type and edit and type and write and type and type and type.

I decided I was qualified, because we were talking about THE NEW YORK POST, home of Milton Gross and Pete Hamill and Larry Merchant and Jimmy Wechsler and Maury Allen and Vic Ziegel and Jimmy Cannon and Leonard Lyons and . . . yeah, you bet I’m qualified.

The sports editor at the New York Post was Ike Gellis, and my friend’s mom was married to his doctor. Gellis was a lifelong chain smoker who had pretty much every ailment associated with tobacco, so he saw my friend’s dad just about every other day. Gellis and the good doctor also shared a love for the ponies, so they spoke on the phone at least nine times a day — before every race at Aqueduct, Belmont or Saratoga.

I was to meet with Gellis the next morning.

But first there was the issue of my hair, which ran well below the shoulder and definitely was not going to make the right impression among the socially conservative sports journalism crowd. Jocks and the people who write about them do not have long hair.

I hightailed it to the Town & Country Plaza and walked into the barber shop for the first time in more than two years. He gleefully chopped off pretty much everything and then charged me an extra two bucks — a long hair surcharge. I think he charged by the inch.

I caught a flight home to New York and showed up at the Post — on South Street in Manhattan — the next morning for my first serious job interview ever. For the first time, we were not talking summer job.

I met with Gellis and the assistant sports editor, Sid Friedlander, and some others in the office, and they gave me the test. Turned out I could spell. Turned out I could type. Turned out I could even edit. They gave me a piece to work on and I rewrote the lede, and I found out later that it was written by William H. Rudy, probably the best thoroughbred racing writer in New York. Turned out I had chutzpah.

I felt everything was going well, and then Friedlander came over with the final portion of the exam.

OK kid, he said . . . You know how to spell. You know how to write. You know how to type. You know how to edit . . .

But what do you know about sports?

It was a good question. I was editor of the Hobart & William Smith Herald, so my writing was pretty much dedicated to the usual college newspaper material — ending war and stuff, forcing Nixon to resign and bringing the U.S. government to its knees.

But, I told Friedlander, I love sports. I read sports. I watch sports. I’ve always been a huge fan. (I. Want. This. Job.)

Well, says Friedlander, winding up for his Jeopardy pitch, I’ll give you an example.

What does the name Three Finger Brown mean to you?

I looked him straight in the eye and said, “Turn-of-the-century pitcher. Chicago. First name was Mordecai.”

Sid’s next question was, “When can you start?”